Boy bands have tours and billboards; presidential candidates have campaign trails and polls. Both often lack substance, yet are filled with sound bites that become sensationalized public distractions.

As musician Trevor Dunn once pointed out: “Pop culture is not about depth. It's about marketing, supply and demand, consumerism.” Similarly, political pop culture, now more than ever, has become a conduit for marketed slogans and catchphrases intended to sell candidates’ ideologies.

The modern history of political pop culture dates back to America’s first televised presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon on September 26, 1960. Those who watched the debate on television overwhelmingly reported that Kennedy had won, while those who listened on the radio handed the debate to Nixon. Allegedly, this disparity was due to the physical appearance of the two candidates on TV: Kennedy exuded a confident poise and Nixon broke out in a nervous sweat.

As a result of effective campaigning, voter turnout has steadily increased over the past ten elections from an average of 68 million Americans in 1960 to 132 million Americans in 2008. While strategic marketing and messaging is largely responsible, it should not take away from candidates’ responsibility to provide Americans with detailed, transparent policy proposals. While Obama wants to cut taxes for the middle class and improve education, Romney talks about cutting taxes by 20 percent across the board; but neither clearly explains how they intend on accomplishing their pledges.

Also, thanks to America’s shameless obsession with glitzy balloons, candidates become heavily marketed products, replete with punchy points, humorous gaffes, and improvised memes. Obama becomes your best friend and a cool liberal icon, while Romney turns into a savvy businessman who knows how to get the U.S. economy thriving again.

Unfortunately, these popularized personas are just ideas, and neither Obama nor Romney become strong presidential candidates who provide concrete solutions. If they did provide such solutions, and by some chance Americans forgot, it would probably be blamed on a severe case of Romnesia, a term coined by Obama, or a lack of adequate Obamacare coverage, a term adopted by Republicans.

In Robert Draper's “They Retort, You Decide,” debate coach Brett O'Donnell, said that it's about looking "presidential." Debates provide a "messaging opportunity," and it's largely about, “firing off catchy rhetoric that may or may not be technically accurate.”

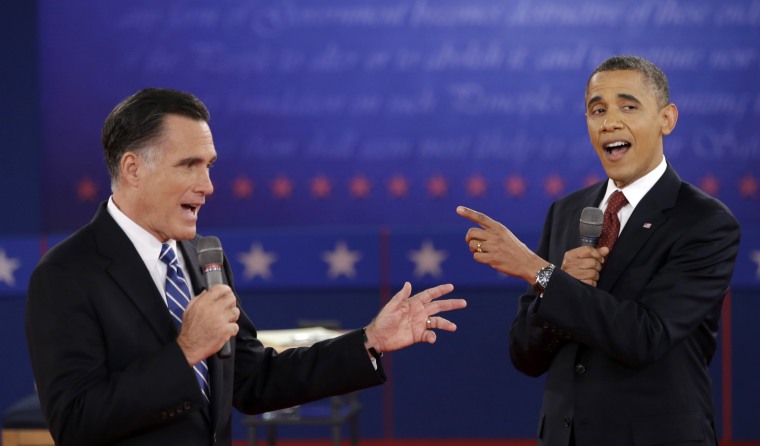

For the Obama-Romney race, it’s also about being cool and delivering lines that last, while the public scrutinizes who makes the worst gaffe.

During the second presidential debate, when asked about equal pay, Romney’s response, which included the phrase, “whole binders full of women,” was a gift to social media heathens. Instantaneously, comical memes stormed the web.

Then, in the foreign policy debate, Romney criticized Obama for leaving the U.S. Navy with fewer than 313 ships. Obama responded, “We also have fewer horses and bayonets.” Of course, the “horses and bayonets” line quickly became political fodder and assumed more relevance than the crucial topic of military expansion altogether.

With the debates officially over and only 13 days until Election Day, all we have left are the post-debate conversations that will continue to be dwarfed by the inconsequential rhetoric of political pop culture.