The day before the election, President Barack Obama was preparing to speak in Ohio when state Republicans tweeted that they had knocked on 75,000 doors that day. Campaign aides told Obama they had knocked on 376,000 doors that day, according to a campaign staffer who recounted the story to reporters.

The president smiled widely. “That’s my team,” he said.

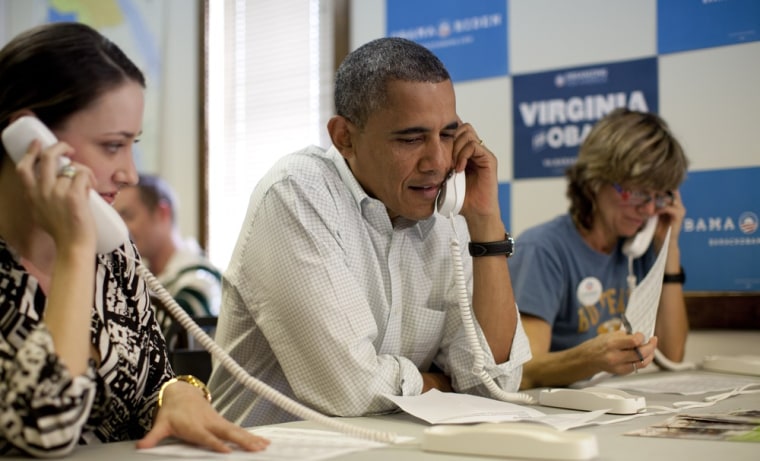

Through investing heavily in a ground game devised by field organizing veterans and honed over the last five years, the president’s campaign used voter-to-voter contact, a sprawling physical campaign, and personalized outreach to help the president compete against the financial advantage of the his opponent.

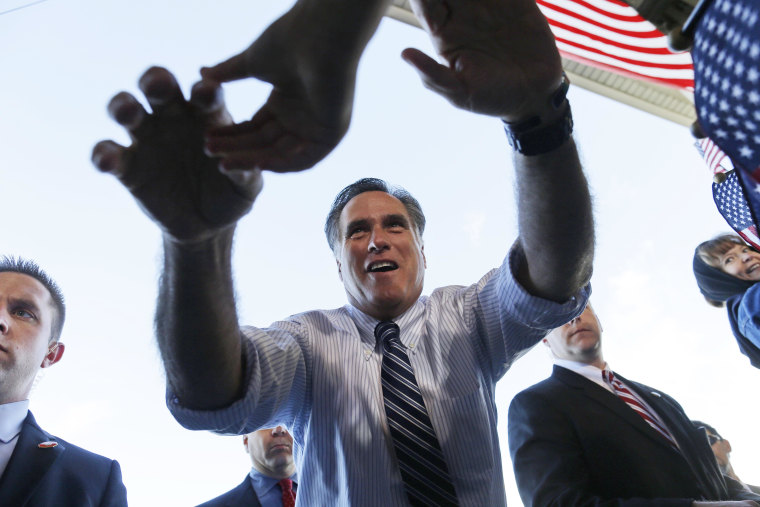

In Ohio, Gov. Mitt Romney and his allies spent $100 million on advertising, while the president and his allies spent $91 million, according to the latest numbers (through mid-October) disclosed to the Federal Election Commission.

Nationwide, the former governor and his allies spent $137 million more than the president's team on advertising. But the president won the pivotal state -- and the country -- through investing in human resources: his field team.

Romney may have won the fundraising game, but Obama won the ground game. The president recognized the campaign's significant contributions in a tearful thank-you speech Wednesday.

Team Obama vs. Team Romney

Obama’s campaign was cash-rich and staff-heavy. It had 901 staffers in August with a reportedly average salary of $36,000. Volunteers were plentiful, outreach was a primary focus.

Romney’s campaign lacked the cash advantage and was small—just 403 staffers were on payroll in August—but well-paid, with an average salary of $77,000, according to a Los Angeles Times breakdown. The campaign disputed that figure saying the average salary is $51,000, because numbers were skewed by back-payments.

Where Team Romney held the finance advantage was in an army of well-funded conservative super PACs that spent more than $400 million on his behalf. As super PACs cannot communicate or coordinate with the campaigns, they tend to focus their funds in advertising.

“This is really the first post-Citizens United election,” said Steven Jarding, a former campaign director and adviser for the likes of John Edwards and Tom Daschle, referring to the Supreme Court ruling that allowed uncapped donations by individuals and corporations to political action committees.

Jarding, who now teaches public policy at Harvard, noted that Democrats possess a long history of successful field organizing, but explained that the Citizens United ruling has given Republicans a huge cash advantage. That cash, though, is funneled into advertising and mailers rather than the ground game.

“PACs tend to be run by an elite group of individuals who tend to not get down into the weeds,” he said. “They believe the biggest bang for their dollar is to maximize the airwaves.”

Romney’s campaign, and groups working on his behalf, bought hundreds of millions of more advertising than the president’s campaign and his outside allies – $137 million more, to be exact, according to numbers compiled in late October by NBC News.

“It’s a dangerous perception to say we’re just gonna buy our way in. When you inundate seven states with millions of ads, it’s overkill, you have a point of diminished returns,” Jarding said. “But the ground game is going to pay dividends.”

In fact, a report released by the Sunlight Foundation this week showed that despite pumping more than $100 million into the general election, the conservative, Karl-Rove-backed super PAC American Crossroads reaped only a 1.3% return on its investment.

It's possible that Romney's super PAC focus may have obstructed the Republican’s ground mobilization in this election. But as the first presidential election post-Citizens United, it's likely these techniques will only be honed and improved, Jarding said.

“It’s harder to [campaign on the ground as a super PAC] because you can’t have collusion, but my sense is there may be some adjustment in the next cycle, in 2016," he said. "They’re going to have a full four years to figure it out.”

Retail Politics

Ganz is the seasoned field organizer who developed the ground game that Obama first embraced in 2008 and refined this year; he served the Obama campaign as an adviser in 2007. Obama’s re-election field director, Jeremy Bird, studied under Ganz as a student at Harvard and as a young field organizer on the Howard Dean campaign in 2003.

The Obama ground game is based on hyper-local organizing tactics, Ganz explained, where the campaigns recruit, train, and place volunteers from within targeted, battleground communities into teams.

“So I [as an Obama volunteer] become part of a team working with my neighbors to get out the rest of my neighbors and we’re responsible for a certain number of votes. Now we have a chunk of this campaign that we’re responsible for in our community. That’s about as close as you can get to when politics were done on a local level.”

The campaign looks to mobilize and motivate, not only getting voters on board with the president but by convincing them their vote matters and getting them to the poll. It utilizes shame and peer pressure on people to vote through everything from personal voter outreach to targeted social media. (Did you notice those constant Facebook notifications and emails on Tuesday from the Obama campaign asking voters to ask their battleground-state friends to vote?)

“It matters if you’re contacted by another person. It matters even more if it’s a person you know,” Ganz said. “It matters even more if your neighbors know whether you’re voting or not.”

The other typical type of campaign, Ganz explains, is a marketing campaign, like the one Romney and his super PAC allies seems to have employed, where TV advertisements and mailers replace door-to-door outreach and well-paid marketers take precedence over massive volunteer networks.

Still, Romney's ground game improved drastically upon Sen. John McCain's in 2008.

Romney’s outreach was delegated to the Republican National Committee, whose large, more localized staff they hoped would help them compete with Obama’s resurrected 2008 infrastructure and ground team in a shorter period of time. The RNC hit snags when they had to fire the consultant charged with registering voters in five swing states after allegations of fraud surfaced.

Team Romney bragged of a considerable ground game. By October, the it announced they had made 35 million voter contacts, including 6.5 million door knocks, representing three times as many door knocks as made by Republicans in all of 2008. Former Christian Coalition director Ralph Reed raised and spent millions in battleground states to try and bring out the religious right vote. By the end of the campaign, they had made made 50 million voter contacts through phone calls and door knocks.

In the final week, the Obama campaign said it had made 125 million voter contacts.