"When you raise the price of employment, guess what happens? You get less of it," said House Speaker John Boehner last week. That, in a nutshell, is the entirety of the Republican argument against President Obama's proposed minimum wage increase.

Not so, say Paul Krugman in a Monday New York Times column. While Boehner's argument has a certain clean, spartan logic to it, Krugman says it goes against the empirical evidence. "[H]uman relationships involved in hiring and firing are inevitably more complex than markets for mere commodities," he writes. "And one byproduct of this human complexity seems to be that modest increases in wages for the least-paid don’t necessarily reduce the number of jobs."

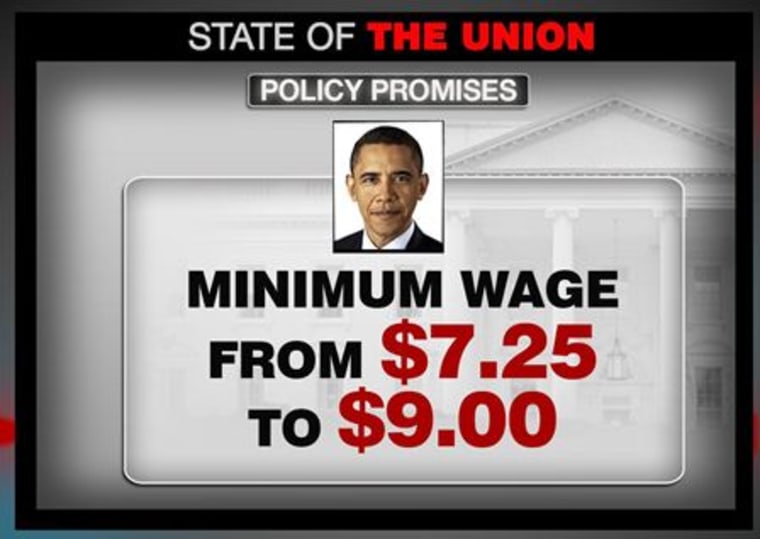

Of course, the operative word is necessarily. Empirical research on the subject is inconclusive; no one knows for sure whether raising the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $9.00 an hour would have an appreciable affect on employment. As with so many economic adjustments, the question is one of risk assessment rather than certain outcomes.

But say Boehner's right, and we know for certain that a minimum wage hike will have an overall negative impact on employment. Unless the effect is particularly severe, it could still be well worth it.

After all, a minimum wage hike is unlikely to kill solid, middle-class jobs. Instead, it would overwhelmingly affect minimum wage jobs, or jobs which pay close to minimum wage. With the federal minimum wage being what it is, that amounts to poverty-level compensation: $15,080 per year for an employee who works forty hours a week, every single week of the year, without vacation or unpaid sick days. And that's before we factor in wage theft, which is endemic among low-wage workplaces in the United States.

By comparison, the average unemployment insurance disbursement in 2012 was around $300 a week, which adds up to $15,600 per year. Even a meager unemployment check is sometimes worth more money than a full-time minimum wage job. That helps to explain why so many low-wage workers can only get by with the help of state assistance such as food stamps—according to the USDA, 41% of food stamp recipients live in households with full- or part-time workers.

These are the jobs we risk for an opportunity to raise the overall wage floor, and to ensure that this wage floor continues to rise with the cost of living. Critics of the proposed minimum wage increase may reply that a poverty-level wage is at least better than no wage at all—and they'd be right. But the fact that poverty-level wages are even an observable phenomenon in a society with our wealth is a sort of economic crime. The question is not how to rescue jobs which pay that little, but how to make sure that no one is ever forced to work in such conditions. A minimum wage increase is a positive but insufficient step in the right direction.