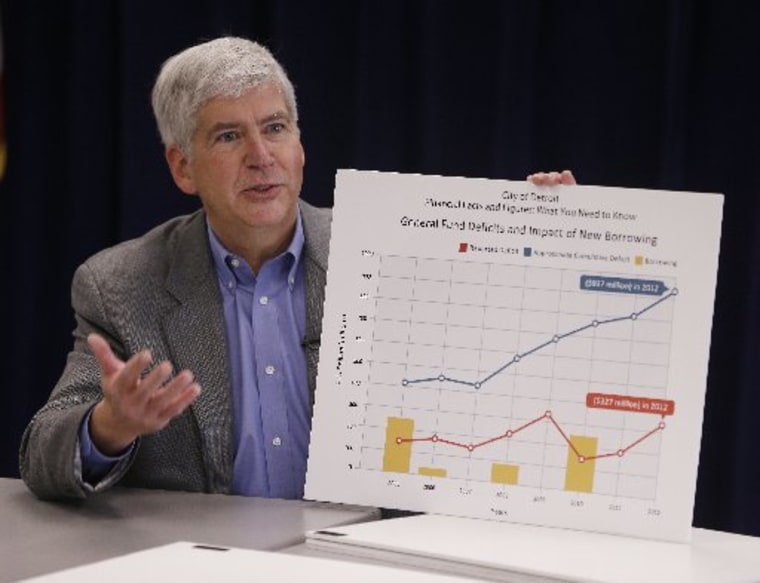

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder is right about one thing: Detroit is in a serious financial emergency. In fact, according to a recent audit of Detroit's finances, the city is lodged at the bottom of a $327 million budget hole. But while Snyder has correctly identified an emergency, he's rarely discussed the roots of the emergency.

Those root causes are hardly a moot point, considering that the crisis is the reason why Snyder intends to appoint an Emergency Manager (EM) to govern the city. EMs are state appointees who have the power to overrule the local government, and even unilaterally suspend or modify union contracts. As msnbc reported on Monday, EMs in other Michigan cities have consistently used this power to lay off city employees, undermine public sector unions, and privatize public services.

Whoever Snyder appoints as EM in Detroit will likely follow that trend and force public sector workers to make considerable sacrifices in the name of fiscal solvency. If Snyder's EM balances the city's budget, he will probably do so in large part on the backs of public sector union members.

But it's unclear why union members should be asked to give up so much. It's not like lavish union contracts caused Detroit's financial crisis; in fact, unions have made significant concessions in recent negotiations, including an across-the-board 10% pay cut. The major perpetrators behind the city's budget crisis are, in fact, the banks—and they're precisely the institutions which are least likely to suffer the consequences.

On Monday, independent journalist David Dayen wrote about the role the housing crisis played in ruining Detroit's finances. "Predatory loans trapped borrowers into monthly mortgage rates they couldn’t pay, with lenders particularly targeting lower-income minority areas like Detroit. Many of those homeowners are gone now, evicted from their properties," wrote Dayen. He goes on:

In a foreclosure, the property reverts back to the bank, which then becomes responsible for all maintenance and upkeep, as well as any fees. Some banks simply ignore these responsibilities and refuse to pay taxes or keep the vacant property in good order. The more clever banks stick evicted homeowners with the bill.Across the country and particularly in Detroit, banks have engaged in “walkaways,” where they start foreclosure proceedings but then find them too costly to complete. They choose not to finish the legal steps to foreclosure, leaving the properties vacant. Banks that walk away from homes do not have to notify the city, or even the borrower, that they have abandoned the foreclosure process. Borrowers kicked out of their homes then find themselves still responsible for property tax payments.

"A 2010 report of the Government Accountability Office found 500 bank walkaways in just four Detroit zip codes," writes Dayen. It's hard to say just how much money the city has lost as a result of these "walkaways," but according to the Detroit News, $246.5 million in property taxes were left uncollected in the past year alone.

Walkaways aren't the only way in which major banks have gouged the city's finances: According to a 2011 financial report, Detroit also owes $3.8 billion in interest rate swaps. An interest rate swap is a type of financial instrument by which cities exchange the variable interest rates on their municipal bonds for the fixed interest rates offered by banks. However, when the federal government drove down the variable interest rate in the aftermath of the financial crisis, cities were left with a comparatively stratospheric fixed interest rate.

Many of those variable interest rates are tied to something called the London Interbank Offered Rate, or LIBOR. The LIBOR number, regularly updated, refers to the rate of interest at which the biggest London banks pay when they borrow from one another. Recently, as many as 20 of the biggest banks in London have been accused of secretly rigging the LIBOR rate, driving it down so that they could pay lower interest rates.

As it turns out, the variable interest rates involved in interest rate swaps are often pegged to LIBOR—meaning that, even as they stand accused of LIBOR manipulation, banks which hold interest-rate swaps stand to make a fortune off the extremely low variable rates which they allegedly manipulated. While the cities which hold interest rate swaps owed the banks the same flat rate which they always had, the banks, in turn, owed practically nothing. In fact, eight counties in the state of California recently sued two major banks, saying "they were cheated out of higher interest payments on investments such as interest-rate swaps and corporate bonds tied to Libor."

Again, it's difficult to measure how much LIBOR manipulation has cost the city of Detroit. But what we do know is that the banks are being asked to sacrifice nothing in order to keep Detroit afloat, even as working-class city employees are told that a 10% pay cut is an insufficient concession on their part.