Growing up, Brianna Mullen watched her parents lose their jobs and declare bankruptcy twice, until ultimately they were forced out of their Bay Area home because of foreclosure. Now, the 20-year-old is determined to avoid a similar fate.

A rising junior at the University of California-Berkeley, Mullen is working two jobs while she's studying education policy and urban planning, trying to keep her debt load to a minimum.

But unless Congress acts before July 1, interest rates are set to double on the subsidized federal loan that Mullen has relied on every year to finance her education: By her estimate, she'll owe $1,500 more in interest payments.

For Mullen, who was kicked out of her home at age 17 and is now financially independent, "it's frightening to think about. There's no going back to mom and dad," she said. "Fifteen hundred dollars—that's two months' rent for me."

July 1 rates go up

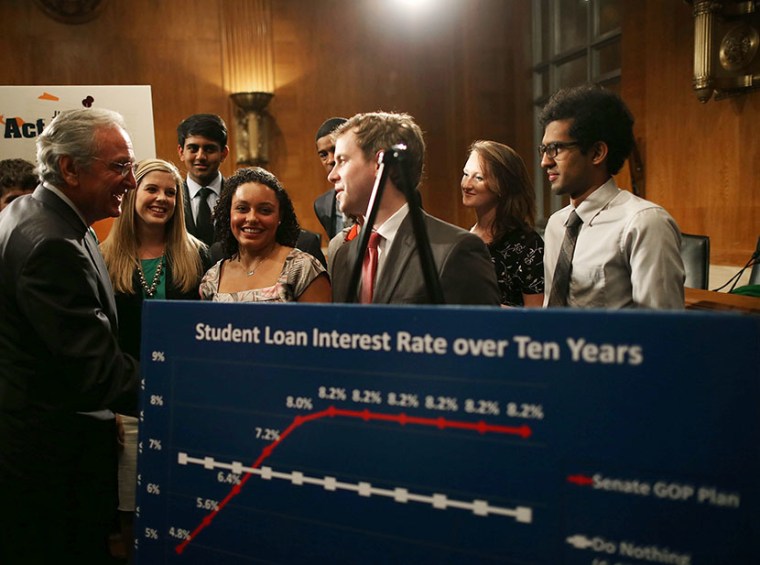

Both Democrats and Republicans agree that they want to avoid such an outcome for student borrowers like Mullen, and NBC News has learned that a bipartisan agreement has been reached in the Senate. Student loan interest rates were scheduled to rise from 3.4% to 6.8% on July 1. And even if a deal does pass, it's still highly likely that future students will pay more in interest to the federal government as legislators continue to insist on budget austerity.

About 95% of all college loans are issued by the federal government, which provides significantly lower interest rates than private borrowers, typically without requiring a credit check. The rising interest rates would specifically hit the low-income students who receive subsidized Stafford loans, which go to borrowers with demonstrated financial need and don't require interest payments until after they leave school.

The rising rates won't affect the 7.2 million students who took out these subsidized Stafford loans this year—only future borrowers. For those who borrow the maximum amount of $19,000 over four years will have to pay an additional $3,834 in interest payments over 10 years if rates are allowed to double to 6.8%, according to the Congressional Research Service.

With student debt loads averaging $27,253 in 2012, that might seem like a modest increase—particularly compared to the skyrocketing tuition costs. Between 2000 and 2010, tuition and board at public universities rose a whopping 42%, and the cost of attending private non-profit colleges rose 31%, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. So lower interest rates won't put much of a dent in making college more affordable. "What you pay on the loan is mostly driven by what you borrow, not the interest rate," says Jason Delisle, director of the Federal Education Budget Project at the New America Foundation.

But students and their advocates insist that every dollar of additional debt matters, and that Congress is uniquely positioned to act on the issue right now. "To allow something in our control to potentially double is insanity," said Sujatha Jahagirdar, political director for Student PIRGs, an advocacy group that's been lobbying for lower rates.

Many proposals, one deadline

On the surface, the differences between lawmakers may seem technical: President Obama, House Republicans, and a group of Senate Republicans have all endorsed plans that would peg Stafford student loans to the 10-year Treasury rate, plus an additional fixed amount ranging from 0.93 percentage points (Obama) to 3 percentage points (Senate GOP group). A group of Democratic senators led by Sens. Jack Reed of Rhode Island and Dick Durbin of Illinois endorsed a plan that would peg the loans to the three-month Treasury rate, plus an estimated 2 percentage points. All of these proposals would reform the system from a fixed rate determined by Congress to a variable one that would depend on the market.

But the difference of a few percentage points on interest rates means billions of dollars in the long term. And the larger question of how much should come from students' pocketbooks and how much from the government has caused major consternation in the Senate, where the action has moved since House Republicans passed their plan in late May.

Democrats have criticized the House Republican plan for raising costs on low-income student borrowers and allowing rates to fluctuate on the same loan. The leading House Republican on the issue, Minnesota Rep. John Kline, defends the bill as a long-term solution, in contrast to the short-term fix that Senate Democrats initially fought for. "Students in many cases are confused about what's going to be affected," said Kline, chair of the House Education and Workforce Committee, explaining that interest rates would only rise on future loans.

More unusually, Senate Democrats have also found themselves at odds with the White House proposal. While the baseline rate is lower than the House GOP's, the administration's plan doesn't include a cap on interest rates—a point that Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin, who chairs the Senate committee on education and health, is insisting upon.

Without a cap, Harkin points out, student interest rates could skyrocket if the Treasury rate spikes in the future. But a rate cap would also require more government spending on Stafford loans in the long term if the baseline rate is kept very low.

That's something neither the administration nor Congress seems very eager to do.

Advocates remain skeptical of a deal

House Republicans want to use student loan reform for $3.7 billion in deficit reduction, while the CBO estimates that Obama's student loan reform plan would save $6.7 billion over 10 years (though he would invest most of that in other higher education programs). Senate Democrats failed to pass a short-term extension offset by closing tax loopholes. And Maine independent Sen. Angus King, who's working on the Senate's bipartisan agreement, aims for the final plan to be deficit-neutral—something that's a pre-condition for passage in the House.

"We have obligations not only just to current students and those starting school, but obligations to everyone. Running a heavy deficit—that's a debt they will owe as well," said Kline.

There's still hope for an eleventh-hour deal, but many leading advocates remain skeptical. "Unfortunately, I think the most likely outcome this week is that interest rates will go up on July 1," said David Bergeron, a former Education Department official and vice-president at the Center for American Progress. Last year, legislators simply punted on the issue last year by passing a one-year extension of the 3.4% interest rate, allowing both parties to claim that they were keeping rates low while courting young voters in an election year.

This time around, "there’s not the sense of urgency," said Dexter L. McCoy, 21, Boston University's student body president, who estimates that he'll graduate with some $40,000 in debt.

McCoy recently signed onto a letter from student leaders across the country urging Congress to keep college affordable and has been asking his classmates to lobby their representatives. But he already doubts that low borrowing rates will last much longer—whether Congress decides to act or not.

"At a certain level, we're going to have to accept that they will go up," he said.